The pão-de-ló, or Portuguese sponge cake, is one of the most prolific and irresistible sweets of the Portuguese gastronomic repertoire. It is, at the same time, a tribute to simplicity, consisting of a mixture of solely eggs, sugar, and flour.

It is during Easter that pão-de-ló gathers special attention at the table, in particular in the north of Portugal, where regional recipes thrive. Most families have their own version of pão-de-ló, with slight variations that make it either drier or more moist, softer, or denser, according to personal taste and family tradition.

But unlike what one could imagine, this is no straightforward tale, indeed, it nothing less than a saga. Keep on reading to discover the history behind this cake, the most famous varieties, and also, my grandmother’s pão-de-ló recipe.

Contents | Conteúdos

THE ORIGIN OF SPONGE CAKE (AND PÃO-DE-LÓ)

We should get one thing straight right at the beginning. The cake that the Portuguese call pão-de-ló is not exactly a Portuguese invention; there are similar recipes all throughout Europe, like the English sponge cake, the Italian pan di Spagna, the French génoise (which has butter), or the Sephardic pan de Espana. But where did all these recipes come from?

Well, with the repeated references to Spain, it’s easy to guess that the main theory points out that sponge cake should have been invented in Spain, somewhere in the 16th century, right in the middle of the Renaissance period. In fact, it is proposed that at the time this cake was also known in Portugal as pão de Espanha (bread from Spain) or pão de Castela (bread from Castille).

The popularity of sponge cake in Italy (where it was known as pan di Spagna), more specifically in Sicily, might have been the fruit of the region’s intermittent Spanish domination. Eventually, the appearance and popularization of this recipe in Italy may also be due to the important positions held by Spanish clergymen in Rome, or of the flight of the Jewish people from the Spanish Inquisition.

In Italy, the sponge cake dough was also used as the base for the preparation of biscuits, as one may observe in the monumental “Opera Di M. Bartolomeo Scappi, Cuoco Secreto do Papa Pio V” written in 1570 by Bartolomeo Scappi. There, Scappi mentions the mostaccioli alla Milanese, and then the biscotti alla Savoiarda (now commonly known as ladyfingers, or savoiardi). Maybe the Italians ended up retributing the influence to the Spanish, as our Spanish neighbors call sponge cake bizcocho (i.e. biscuit, in spite of being a cake).

A CAKE FROM THE RENAISSANCE

The Renaissance brought a change of paradigm regarding gastronomy; with the arrival of exotic ingredients from all four corners of the world, with a novel perspective of the impact of food in health, with gastronomy gaining a role as a cultural element, and also as a social differentiator. The interest in the art of cooking intensified, and appetites flourished with a wave of innovation in recipes and techniques, which also led to the publication of multiple cookbooks throughout Europe.

Up until then, most cakes were leavened with baker’s yeast, i.e., with the Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast. In essence, this made cakes little more than sweet bread. The innovation that occurred with the appearance of the sponge cake was that one could make a cake without fermenting it. The act of fermentation was replaced by mechanical airing, i.e., the persistent and prolonged beating of eggs with sugar leads to the incorporation of air bubbles to the cake mix, which will ultimately create the cake’s light and airy texture.

It comes as no surprise that before the invention of the electric mixer, making sponge cake was hard work, as one could easily need to beat the eggs for many minutes or even hours.

Then it was (and is) vital to carefully mix the flour into the mix, combining it slowly with a wooden spoon. This way, you won’t ruin the precious air bubbles, or overdevelop the gluten (otherwise the cake would be elastic). To maintain the dry sponge cake’s structure, many cool down the cake by placing the mold on its side, or upside down, held by a glass bottle or clay pot. With this technical innovation, sponge cake readily entered the recipe-books of several European countries and was adapted and perfected throughout the centuries.

PÃO-DE-LÓ IN PORTUGAL

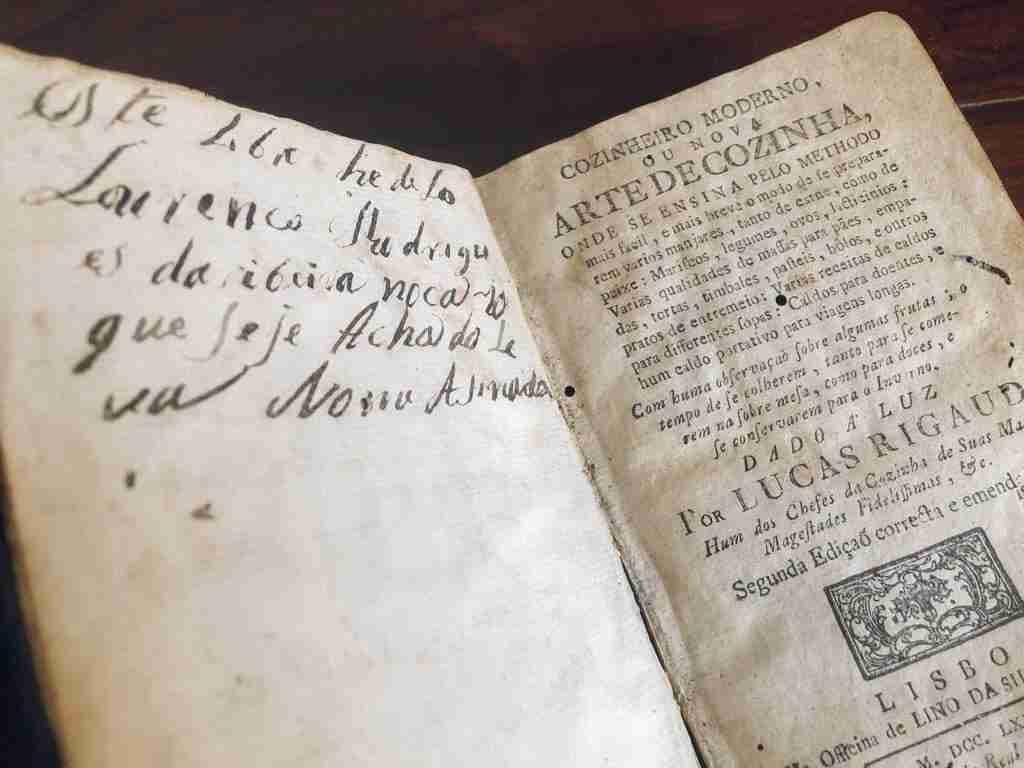

The first known reference to pão-de-ló in Portugal appears in the manuscript of the Infanta D. Maria (1538 – 1577), but it appears to be a simple almond and sugar pudding, and not a cake, in similarity to the recipe written in the first cookbook ever published in Portugal — “Arte de Cozinha” by Domingos Rodrigues (1680) — in its almond “pão-de-ló”. Despite being named pão-de-ló, neither represented pão-de-ló as we know it today; both desserts were solely composed by almond and sugar.

Notwithstanding, Domingos Rodrigues mentions a recipe of “biscoutos de la reina“, known today as ladyfingers or savoirardi, which originated in the Duchy of Savoy and appear in Bartolomeo Scappi’s first cookbook. They are, quite simply, biscuits made of twice-baked sponge cake. Hence we know, at least, that the technique for making sponge cake was already familiar.

Interestingly, in the second cookbook published in Portugal — Cozinheiro Moderno ou a Nova Arte de Cozinha de Lucas Rigaud (1780)— which incorporates many European techniques and recipes, it is possible to find a recipe of “pão de ló ou Bolos de Saboia (Savoy cake)”. Aha, we see Savoy appearing once more. Indeed, here the recipe is very similar to many Portuguese pãe-de-ló, but with the addition of grated lemon peel, preserved orange flowers, and covered with sugar, egg white, and lemon icing.

JOSEFA KNOWS BEST

Perhaps this is the most thrilling chapter of pão-de-ló‘s biography. It isn’t in the books that we find the oldest reference of what we currently know as pão-de-ló, but instead, in paintings. If we observe some of the most relevant pictorial depictions of Portuguese gastronomy, the work of Josepha de Ayala (also known as Josefa d’Óbidos), we will find the pão-de-ló. Individual slices of this fluffy cake, in all its splendor. It is likely that at the time it was still known as pão de Espanha (bread from Spain) or pão de Castela (bread from Castille). And through the richness of Josefa d’Óbidos’ paintings, we can understand that this cake already existed in Portugal in the 17th century, but also due to its prolific appearance in her work, that it must’ve already been quite popular.

“There are the easter folares with their crosses of dough over boiled eggs, the sweet bowl of spaghetti squash jam, the pães-de-ló in their bed of ornate paper, the queijadas, the fartens, the white and red communion wafer, shaped like seafood for the ovos de Aveiro, the grangeias and obreias , and so many other native sweets, light, tasty, and buttery in the shade of the green fava beans and peas that seem to be there so that the sweet things made from sugar smile upon ten generations of our sweet-tooth and glutton descendants.”

Gustavo de Marques Sequeira, “Josepha em Óbidos”

The drier version of pão-de-ló appears clearly in more than one painting, the moist version, not so much. However, it may be the one represented on the left side of the above painting, encased by a wooden box, and punctured by a silver spoon, as some suggest.

... AND MAYBE THE JAPANESE DID TOO?

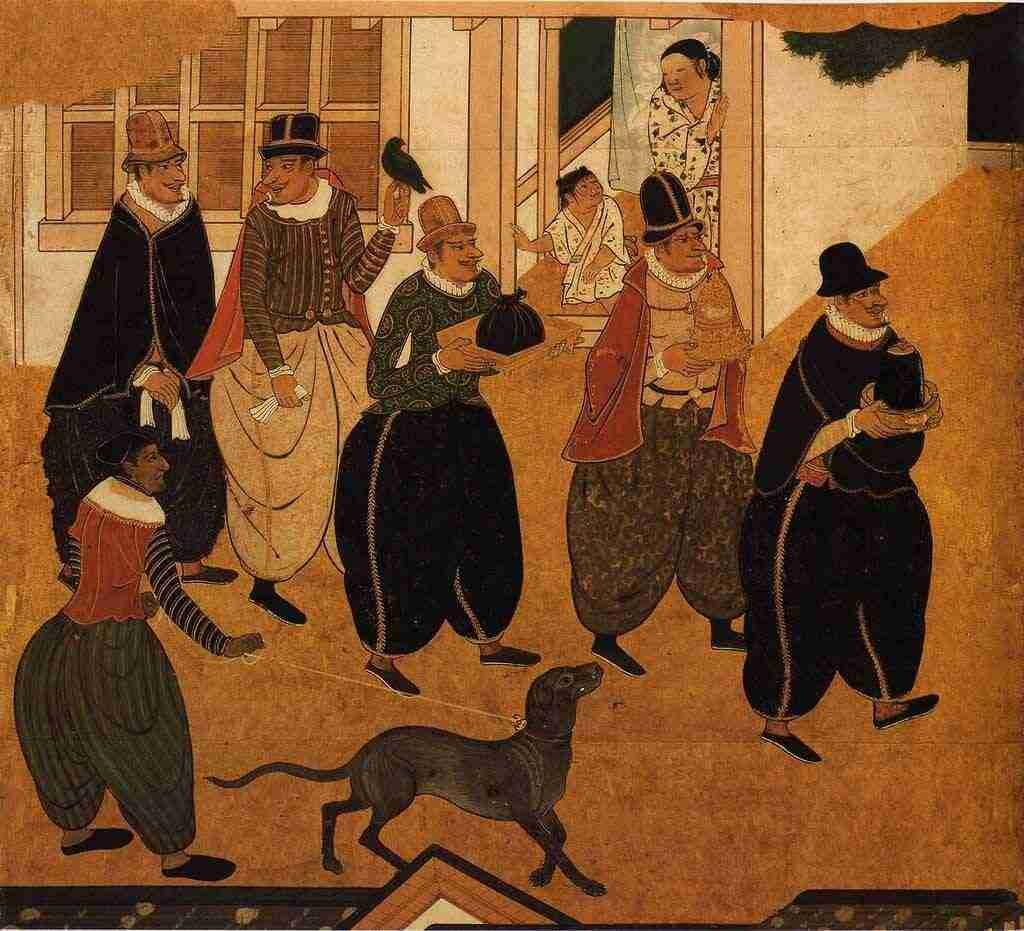

In fact, the popularity of pão-de-ló in Portugal must’ve been seen for quite a while. In the 16th century — specifically between 1543 and 1637/1641, when the Portuguese were cast out of the country — Portuguese merchants and missionaries sailed to the port of Nagasaki in Japan. They left the recipe of pão-de-ló, at the time known as “pão de Castela“. The Japanese soon took it as their own, adapting it and baptizing it as “castella“, also known as “kasutera“. Today, it is still extremely popular and an icon of the region’s pastry. Moreso, the dough of castella is also the base of dorayaki, the famous pancakes with azuki bean paste — yes, those that Doraemon ate.

PÃO-DE-LÓ: A SWEET FROM NORTH TO SOUTH

It’s now time to focus on the many varieties of pão-de-ló we can find throughout Portugal. It’s undoubtedly a popular dessert, especially in the north. There isn’t a lack of regions that have their own version of pão-de-ló — there are several dozens of recipes throughout the country — in spite that many recipes are quite similar. Whoever desires to execute a sweet pilgrimage may easily travel from Alpiarça to Estremadura, from Alfeizerão to Arouca, or from Margaride to Mirandela on the expense of pão-de-ló. In between, there are several desserts that arise from pão-de-ló, such as the cavacas, the sopas douradas, or the barrigas de freira from Monção. But for now, let’s look into the most popular varieties of this cake.

On a side note, when visiting Porto, it’s easy to come across this cake in one of our private food tours or even, for those who love to get their hands on, in a private cooking class where you can make pão-de-ló.

PÃO-DE-LÓ DE MARGARIDE

In the region of Entre Douro e Minho, precisely in the old parish of Margaride in Felgueiras, there comes to light one of the most popular recipes, the pão-de-ló de Margaride. This recipe was developed over two centuries ago by a lady named Clara Maria. After her death, the recipe was undertaken by Leonor Rosa da Silva, who would end up founding the famed Fábrica de Pão-de-ló de Margaride. Later on, with the success of her establishment, Leonor would become Supplier of the Portuguese Royal House. The factory is now a working museum, with a kitchen that preserves the old way of doing things, including an impressive piece of industrial design: the imposing and shiny tiled oven. This pão-de-ló is traditionally made in clay molds wrapped in paper — with the typical hole on top — and presents a very airy and soft texture, with a toasted crust. It should be cut and eaten by hand, and there are many who love it topped with a slice of sheep’s cheese (queijo da Serra).

WHERE TO BUY IT

Fábrica de Pão-de-ló de Margaride

Praça da República, 304

4610-116 Felgueiras

+351 255 312 121

PÃO-DE-LÓ DE ALFEIZERÃO

The pão-de-ló from Alfeizerão is one of the nation’s most desired sweets. Its unique moist crumb melts at every poke of a spoon, being the ultimate sweet tribute to the egg. The flavor and texture are one-of-a-kinds, although its closest cousin can be found in Ovar. The creation of this pão-de-ló is probably rooted in the sweet ordeals of the nuns of the Mosteiro de Santa Maria de Cós. After its extinction in 1834, the recipes were shared with the surrounding population, who saved them and disseminated them. But a curious moment in history changes the recipe and makes this pão-de-ló a lot wetter. In the late 19th century, during a visit of King Carlos I, he is served a mishap undercooked pão-de-ló. The king is marveled and immediately approves the accidental recipe. This honest mistake is readily adopted, for the delight of everyone who tries it. Later, in 1925, the Casa de Pão-de-ló de Alfeizerão is founded. Today, it keeps its mastery in the art of undercooking this delicacy, still made in the typical copper pans.

WHERE TO BUY IT

Casa Pão-de-ló

Largo Pão de Ló

2460-138 Alfeizerão

+ 351 262 999 558

PÃO-DE-LÓ DE OVAR

When we see the points of white almaço paper, held together by a knotted thread, we know that inside we can only find a rich pão-de-ló de Ovar. A thin and lightly toasted crust conceals a runny and generous interior. It shares its humid nature with the pão-de-ló de Alfeizerão and the pão-de-ló de Soure. It is believed that this pão-de-ló may have come from conventual origins. However, Ovar never had a convent or a monastery. That being said, this means that the recipe must have been brought from out of the region. What we do know, is that the pão-de-ló de Ovar was already used as an offering for priests in procession in 1781. In the middle of the 19th century, there were a handful of families that mastered its confection, in particular, the Arrota family, who is still active in the Pão-de-ló São Luiz pastry shop. Today, the pão-de-ló de Ovar is protected with IGP — Protected Geographic Indication.

WHERE TO BUY IT

Pão-de-ló São Luiz

R. Dr. José Falcão, 48

3880-205 Ovar

+351 256 572 656

PÃO-DE-LÓ DE AROUCA

The pão-de-ló de Arouca sets itself apart with its characteristic rectangular shape (like a pound cake), usually presented in syrup-infused slices. This pão-de-ló may have been originally created by the nuns of the Mosteiro de Arouca (closed in 1886), but no one is sure. What we do know for a fact is that the recipe for this pão-de-ló has been held safely in the hands of the family behind Casa de Pão-de-ló de Arouca since 1840.

WHERE TO BUY IT

Casa do Pão-de-ló de Arouca

Cimo do Burgo

4540-204 Burgo

+ 351 256 944 246

BOLINHOL, OU PÃO-DE-LÓ DE VIZELA

From Vizela — a land of old and acclaimed confectionary — comes the bolinhol, a rectangular pão-de-ló covered in a white sheet of sugar syrup. According to those who produce it, the name “bolinhol” comes from the fact that this cake was formerly wrapped in coarse linen cloths (“linhol“) before it was sold in fairs and processions. As for its origin, the recipe was created by Joaquina Ferreira da Silva in the late 19th century. Her family perpetuated the recipe, and later on opened two pastry shops (Kibom and Pão-de-ló Delícia), which are until today the two guardians of Vizela’s valuable sweet heritage. Recently, the municipality of Vizela created an app where, through the use of augmented reality, it’s possible to discover the history of bolinhol, as well as other historical staples of the city.

WHERE TO BUY IT

Casa do Bolinhol – Kibom

Rua Dr. Abilio Torres, 431

Caldas de Vizela

+ 351 253 587 527

Casa Pão-de-ló Delícia

Rua Dr. Abílio Torres, 465

4815-552 Caldas de Vizela

+ 351 253 481 269

PÃO-DE-LÓ DE FIGUEIRÓ DOS VINHOS

The pão-de-ló de Figueiró dos Vinhos also possesses a peculiar physiognomy, as it is baked in a bundt-like mold, acquiring a striking rimmed ring look. It is believed that this recipe first came from the Mosteiro de Santa Clara de Figueiró dos Vinhos, together with other recipes that were passed on by a nun to a family member, when the monastery was about to close. One-hundred and twenty-six years ago, an entrepreneur bought the recipe and started to sell the famed pão-de-ló in the Fábrica de Pão-de-Ló de Santo António dos Milagres. Decades later, arguments amongst families led to a break-up and the posterior creation of Confeitaria Santa Luzia. This pastry shop still produces the famed pão-de-ló using its original mold and recipe.

WHERE TO BUY IT

Confeitaria Santa Luzia – Fábrica de Pão-de-ló de Figueiró dos Vinhos

R. Dr. José Martinho Simões 75

3260-421 Figueiró dos Vinhos

+ 351 236 552 129

MY GRANDMOTHER’S PÃO-DE-LÓ RECIPE (MARGARIDE-STYLE)

300 g of granulated sugar

250 g of all-purpose flour

8 eggs yolks

7 whole eggs

pinch of salt

almaço paper / 2 traditional pão-de-ló molds / clay cup

1. Pre-heat the oven to 160ºC (320ºF)

2. In a traditional clay pão-de-ló mold, lay the clay cup facing down, and wrap the mold in almaço paper.

3. In a bowl, add the whole eggs and the yolks, followed by the sugar, and a pinch of salt.

4. Beat the mix in an electric beater for 30 minutes, until the mix has risen, is very creamy, and whitish. Remove from the beater.

5. Sift the flour. Carefully and progressively add the flour with a wooden spoon, so as to not damage the air bubbles. The batter should turn out homogenous.

6. Pass the batter onto the mold, with the help of your hand.

7. Cover the mold with another overturned clay mold. Put the batter in the oven and bake for 45 minutes at 160ºC (320ºF).

8. Remove from the oven, let cool down for a couple of minutes, and carefully remove the overturned mold. Let the pão-de-ló cool down still inside the mold, which should be slightly tilted. Otherwise, turn it upside down, supported by the clay cup in the middle, so the pão-de-ló doesn’t fall.

some references

Castella, K. (2010) A World of Cake. Storey Publishing.

Humble, N. (2010) Cake: A Global History. The Edible Series. Reaktion Books.

Krondi, M. (2011) Sweet Invention: A History of Dessert. Chicago Review Press.

Modesto, M. L. (1983) Cozinha Tradicional Portuguesa. 4ª Edição. Verbo.

Produtos Tradicionais Portugueses, Lisboa, DGDR, 2001

http://www.virgiliogomes.com/index.php/cronicas/446-pao-de-lo

2 replies on “Pão-de-ló: history & recipe of Portugal’s favorite cake“